Representing decimal numbers exactly

Recently, I came across an article, highlighting how quickly and dramatically floating point roundoff errors can cause things to fall apart, given the right conditions1, in our modern programming languages.

A representation problem

Modern computer use binary representation to store decimals. That’s mean they can only use a combination of $2^n$.

For example 101.10 is 5.5 in binary ($4 + 1 + \frac{1}{2}$).

| 1 | 0 | 1 | . | 1 | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 2 | 1 | . | $\frac{1}{2}$ | $\frac{1}{4}$ |

| $2^{2}$ | $2^{1}$ | $2^{0}$ | $2^{-1}$ | $2^{-2}$ |

But now, let’s try to represent 0.1, in binary.

\[2^{-4} + 2^{-5} = 0.09375~\text{(not enough)}\\ 2^{-4} + 2^{-5} + 2^{-6} = 0.109375~\text{(too much)}\\ 2^{-4} + 2^{-5} + 2^{-8} = 0.09765625~\text{(not enough)}\\ ...\]We could go continue like this for ages, and still only approximate 0.1.

The problem lies in the fact our metric system uses base 10 fractions, known as decimals, but floating-point numbers are usually represented as base 2 fractions.

Unfortunately, most decimal fractions cannot be represented exactly as binary fractions. A consequence is that, in general, the decimal floating-point numbers you enter are only approximated by the binary floating-point numbers actually stored in the machine.

Let’s illustrate with a simple example, in Swift.

let a: Float = 0.1

let b: Double = 0.1The value of a and b, if we print it usually, is 0.1.

However it’s easy to forget that the actual stored value is an approximation to the original decimal fraction. Printing more digits, we would see this.

(a) 0.10000000149011611938

(b) 0.10000000000000000555

The value is not exactly what we hoped. The same kind of things is observable in all languages that support IEEE-754 floating-point arithmetic.

Muller’s Recurrence

We could easily argue that we usually don’t need that much precision, and that the representation produced is generally enough for us. This is true. But sometimes when the right conditions are met, floating-point representation might break and produces unexpected results.

Jean-Michel Muller is a French computer scientist specialized in finding ways to break computers using math. One of his best-known problems is his recurrence formula.

\[f(y,z) = 108-\frac{815/1500z}{y}\\ x_0 = 4\\ x_1 = 4.25\\ x_n = f(x_{n-1}, x_{n-2})\]We’re going to compute $x_{n}$ for a large value of $n$ and try to infer the limit. Let’s begin with $n = 25$.

First, we define a generic Swift code that implements the formula, and the main of our program.

func f<T>(y: T, z: T) -> T {

return 108 - (815-1500/z)/y

}

func xvalues<T>(n: Int) -> [T] {

var xi: [T] = [T(4), T(17)/T(4)]

guard n > 2 else {

return xi

}

for i in 2..<n {

xi.append(f(y: xi[i-1], z: xi[i-2]))

}

return xi

}

let N: Int = 25

let xi = xvalues(n: N)

for i in 0..<N {

print(String(format: "%i | %@", i, xi[i].description))

}We now use this with the double floating point arithmetic implementation of Swift, Double.

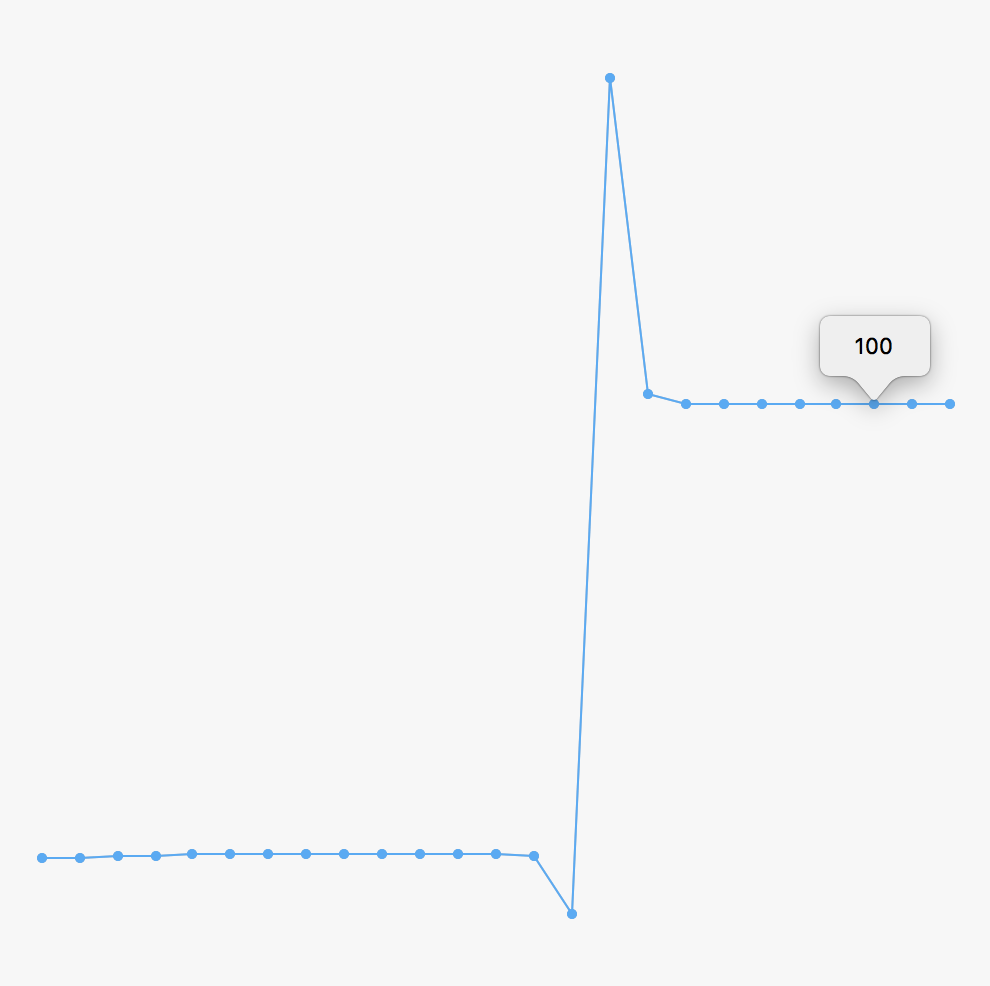

| $i$ | $x_i$ |

|---|---|

| 0 | 4.0 |

| 1 | 4.25 |

| 2 | 4.470588235294116 |

| 3 | 4.6447368421052175 |

| 4 | 4.770538243625083 |

| 5 | 4.855700712568563 |

| 6 | 4.91084749866063 |

| 7 | 4.945537395530508 |

| 8 | 4.966962408040999 |

| 9 | 4.980042204293014 |

| 10 | 4.987909232795786 |

| 11 | 4.991362641314552 |

| 12 | 4.967455095552268 |

| 13 | 4.42969049830883 |

| 14 | -7.817236578459315 |

| 15 | 168.93916767106458 |

| 16 | 102.03996315205927 |

| 17 | 100.0999475162497 |

| 18 | 100.00499204097244 |

| 19 | 100.0002495792373 |

| 20 | 100.00001247862016 |

| 21 | 100.00000062392161 |

| 22 | 100.0000000311958 |

| 23 | 100.00000000155978 |

| 24 | 100.00000000007799 |

With this precision, as $i$ increases, the result converges toward 100. Great, we found the limit!

Unfortunately, this recurrence actually converges to 5.

Why this gigantic round-off error?

There are two main reasons: the design of this formula and the way the computer store the floating point number.

A computer has a finite memory and we saw earlier, they represent numbers a combination of $2^n$. This limited memory requires the need to make trades-off, especially regarding the number of combinations. The number of combinations defines the “precision” of the number it represents. For example Float has about 6 digits precision whereas Double has about 15 digits precision.

Go back to the representation of 0.1 and count the numbers of zeros after the dot, you’ll retrieve these numbers.

We could have used Float80 or Decimal, but they only have a few more digits precision. We would have hit the same limit.

Muller designed his recurrence to produce numbers with an increasing number of digits. The first values of the recurrence can be represented with our classic floating-point types. At a given point, the number cannot be represented exactly, and has to be rounded.

The recurrence is also designed so that a slight rounding error produces a tremendous round-off error. This happens when we wit the $15^{th}$ iteration in our example.

Fixed-point representation

Another classical representation of number is fixed-point. A value of a fixed-point is an integer that is scaled by a factor. This factor is the same for all number. And so the scaling factor defines the range of numbers you can represent.

For example, 1 234 000 can be represented as 1234 by a factor of 1000.

But does fixed-point solves our rounding problem? The short answer is no.

Same as floating-point number, fixed-point is limited by memory.

Neither fixed point nor floating point are immune to Muller’s recurrence. Both will eventually produce the wrong answer. The only question you should ask yourself is “when?”.

Fractional’s representation

Since storing decimals is hard, why not using a method, like fixed-point, that can store without producing an error?

While digging, I stumble upon Lisp and one of his dialect, Clojure. Clojure choose to represent integer division as fractions. So why not use the same technique to our little problem? Using fractions as inputs just treats everything as a fraction, avoiding the problem of decimals.

Same as before, we run the program but now using fractions of Int.

| $i$ | $x_i$ | ~$x_i$ |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | ~4 |

| 1 | $\frac{17}{4}$ | ~4.25 |

| 2 | $\frac{76}{17}$ | ~4.4705882352941176470588235294117647058 |

| 3 | $\frac{353}{76}$ | ~4.6447368421052631578947368421052631578 |

| 4 | $\frac{1684}{353}$ | ~4.7705382436260623229461756373937677053 |

| 5 | $\frac{8177}{1684}$ | ~4.8557007125890736342042755344418052256 |

| 6 | $\frac{40156}{8177}$ | ~4.9108474990827932004402592637886755533 |

| 7 | $\frac{198593}{40156}$ | ~4.9455374041239167247733838031676461798 |

| 8 | $\frac{986404}{198593}$ | ~4.9669625817627005987119384872578590383 |

| 9 | $\frac{4912337}{986404}$ | ~4.9800457013556311612686079942903718963 |

| 10 | $\frac{24502636}{4912337}$ | ~4.9879794484783922601401328939769400999 |

| 11 | $\frac{122336033}{24502636}$ | ~4.9927702880620680974895925483282696604 |

| 12 | $\frac{611148724}{122336033}$ | ~4.9956558915066340266240282615670560447 |

| 13 | $\frac{3054149297}{611148724}$ | ~4.9973912683813441128938690216425944791 |

| 14 | $\frac{15265963516}{3054149297}$ | ~4.9984339439448169190138971781902382881 |

| 15 | $\frac{76315468673}{15265963516}$ | ~4.9990600719708938678168396062869249162 |

| 16 | $\frac{381534296644}{76315468673}$ | ~4.9994359371468391479978508864997899689 |

| 17 | $\frac{1907542343057}{381534296644}$ | ~4.9996615241037675377868879857270921122 |

| 18 | $\frac{9537324294796}{1907542343057}$ | ~4.9997969007134179126629930746330014204 |

| 19 | $\frac{47685459212513}{9537324294796}$ | ~4.9998781354779312492317320300204045157 |

| 20 | $\frac{238423809278164}{47685459212513}$ | ~4.9999268795045999044664529810255297667 |

| 21 | $\frac{1192108586037617}{238423809278164}$ | ~4.9999561270611577381190152822944886054 |

| 22 | $\frac{5960511549128476}{1192108586037617}$ | ~4.9999736760057124445790151493567643737 |

| 23 | $\frac{29802463602463553}{5960511549128476}$ | ~4.9999842055202727079241797881426658531 |

| 24 | $\frac{149012035582781284}{29802463602463553}$ | ~4.9999905232822276594072074700221895687 |

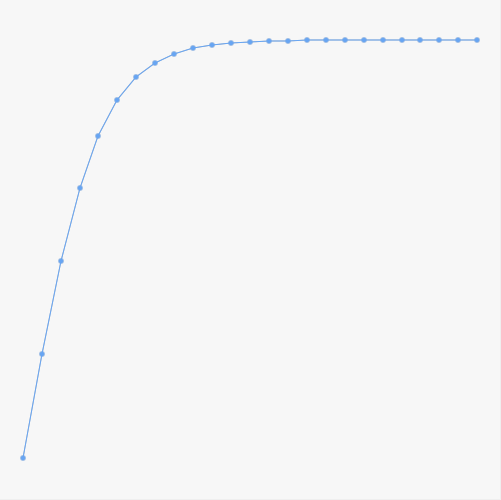

Great! Looks like we’re on the right path! But what happens for $x_{25}$ and so on?

Unfortunately, we hit the Int limit. The numerator can’t be represented using Int and we got a wonderful runtime error.

In order to test our theory, we need an arbitrary-precision arithmetic.

Using this, we are now able to compute much more digits and get an accurate result.

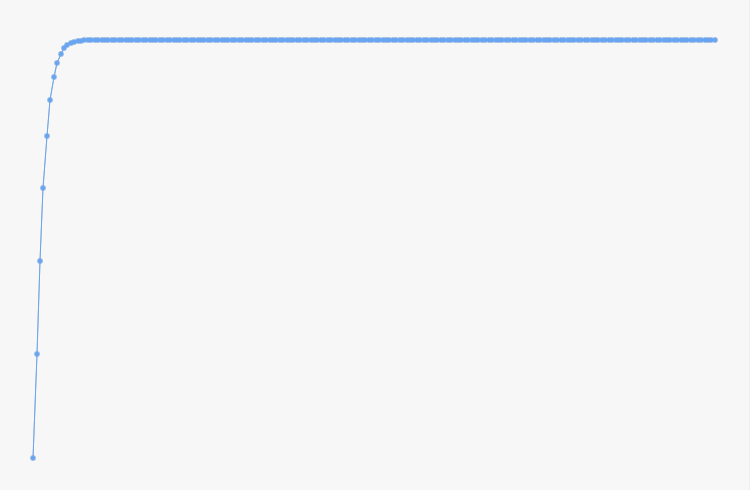

\[x_{100} = \frac{19721522630525295135293987198350753758826715569420223551166026427884564}{3944304526105059027058900515174297154031550406109997834487745707081313}\\ \approx ~4.9999999999999999999998693362752999858\]Precision of the approximation is lost at $x_{173}$ and approximation is completely lost at $x_{273}$.

Some work later, finally, I was able to reach $x_{1000}$.

Wrapping up

Not many languages handle fractions natively although it’s a good way of storing decimals efficiently. Sure, there are some drawbacks, time consuming for example, but if you seek extensive exactness, I encourage you to explore this perspective.

A complete sample project is available if you wish to try it out yourself: https://github.com/gaelfoppolo/SwiftPrecision

Last updated on 15th September 2019